Continuing the session with Video Music Box legend Uncle Ralph McDaniels, he discusses his Classic Concept Productions music video company, dealing with the competition, working on the movie Juice, his Lifer’s Group documentary and why $amhill is ahead of his time.

Robbie: When did it get to the stage where Video Music Box became your full-time job?

Ralph McDaniels: Eventually the station was like, “You’ve got to make a choice. You’re either going to be an engineer or you’re going to do Video Music Box”. From that point on, that was my full-time thing. On the show it was Ralph McDaniels and The Vid Kid – Lionel Martin – he was a guy I grew-up with, who went on to direct some of the best hip-hop and R&B videos in the 80’s and 90’s. I produced and directed, but he directed more than me because I was doing Video Music Box more at the time. We formed a company called Classic Concept Productions. Some of the first videos that we did were MC Shan “Left Me Lonely”, Roxanne Shante “Roxanne’s Revenge”. We worked a lot with Cold Chillin’ Records, so all of Biz Markie’s first videos, all of Big Daddy Kane’s first videos, Kool G Rap and Polo. If it wasn’t for Cold Chillin’, I don’t know if we’d have been as successful in the video business. Before the Genius was the GZA, we did his early videos, Masta Ace, “The Symphony” for Marley Marl. We started to move into some R&B stuff, all of the Bel Biv Devoe stuff. I did all the X-Clan videos, I did Wu-Tang Clan “C.R.E.A.M”, Raekwon “Ice Cream”.

The budgets must have been expanding by the early 90’s.

Labels were starting to spend a couple of dollars on videos, because they knew the importance. By that time, Yo! MTV Raps was out, BET has Rap City, so there was more outlets.

Was that the one where you could pay for videos?

No, that was The Box. Really, The Box was just a rip-off of the name of Video Music Box, because people used to call us “The Box” for short. They created a channel called The Box, and people could request videos and pay $2 or something, so you started to see videos from other markets, especially Florida based rap, the Bass music. Some of those artists really broke on that channel, because The Box was located in Miami. By this time, there are more channels and more videos. Now there were videos coming for everywhere.

Wouldn’t The Box just been filled up with labels paying to put their videos on?

That’s why The Box went away. The record labels started controlling the playlist, because they could just set up a budget and pay for their own videos. There were companies set-up just to do that.

Was Yo! MTV Raps your main competition?

Because Yo! MTV Raps was a national outlet, they could never be as important – regionally – as we were, because we could play local artists that weren’t necessarily on the radio charts but they were known in the New York area and they had good records that people in the area could relate to. Whereas Yo! MTV Raps might pass over that artists because it isn’t a national record yet. We had the ability to go deep. Whenever I felt like Yo! MTV Raps was getting a little buzz, I’d go deep. I’d do events in the heart of Brooklyn, or in the heart of Bed-Stuy, in the heart of Harlem. I was like, “MTV ain’t coming here!” I’d do that things like that just to touch the people a little bit deeper than MTV would. But it was obvious there was money behind Yo! MTV Raps than we had. It was really a product of cable television as well, because now people had cable TV, where they didn’t have that when we started, so there was more competition for the TV stations in general. Now word of mouth isn’t enough, we really gotta go out there and be in the street to promote our events and let people know exactly what we’re doing. I still believe that the streets are still what makes you a hit. Just because you had a video playing on MTV didn’t mean that you were a hit artist if nobody was playing you in the clubs.

In 1998 the station was sold, and it took six months to to find another station. That was like starting over for me, it seemed like an eternity because hip-hop moves so fast. At that time I started working at Hot 97, but I really never liked working at the radio station because I wasn’t getting to play the music I wanted to play. When Hot 97 first started, nobody was listening to that radio station, and then we put them on the air. We did interviews with Funkmaster Flex when Angie Martinez was the intern, and Flex told me one day, “After you put us on TV, that’s when things really jumped off for us. Before that we were doing events and no one was there”.

Going back to your work with Classic Concept, was that your main source of income for a while?

Classic Concept’s was my “main source” as you put it, for quite a few years. We were starting to do some commercial work, which meant more money.There used to be this beer called St. Ides, I did the Wu-Tang version of it [commercials].

How did you cope with limited budgets in the early days of creating music videos?

There were a lot of big production companies doing these videos. They had the resources to do these videos and not spend a lot of money. For us, it was like, “This is how much we’re going to give you”. We were one of the first black production companies. It was an all-black crew. They were like “We’ve never seen this before! We didn’t know they were black lighting guys, black audio guys, black cinematographers”. We’re setting up shop and the cops would come and shut you down, like, “Who’s in charge here?” “We are!” “What? That can’t possibly be!” Creative people just wanted to be down, so that helped out in getting things that we wouldn’t have access to. Get a favor from this person or that person, because they’d never seen a movement like what we were doing with Classic Concept. That helped out and saved us a lot of money. Then we started to get interns and new directors who were coming up. Hype Williams was our assistant, he was a kid. We gave him his first videos that we didn’t have the time to do. Zodiac Fishgreese, Chris Robinson, a bunch of guys that I didn’t even know worked for us! [laughs]

What was the creative process to map out a video?

It was simple then, the record labels didn’t even really understand. We only had to deal with the artist. In the case of someone like Big Daddy Kane, Lionel would sit with Kane, they’d talk about some concepts, then make an agreement and I’d come in and produce. “OK, we can’t do all of that, ‘cos it’s going to cost too much”, or “We can do some of that, let’s think of some ways to make it happen”. Or when I’m working with Nas, he’s like, “Whatever you wanna do, Ralph. I just want it to be street”. I did “It Ain’t Hard To Tell”, so we shot it in different areas in New York and played on the fact that Nas is a good-looking guy, girls are gonna like him, so let’s give him some close-ups so the chicks will dig it. Wu-Tang had an idea that they wanted to shoot in the projects. “As long as we’re representing our hood, that’s all we care about” and they trusted us that it was gonna look right. As time went on, there started to be more people involved in making videos, so now it wasn’t just the director and the artist, there was the manager, product manager, the label exec, some PR firm. So now to get a concept done there’s ten people, and it took away the pureness of it for me. It kinda sucked.

Do you need location permits to shoot in certain areas?

In the beginning, we didn’t know, so we’d just turn on the camera and just show up! As more videos started being shot you had to start getting permits because some directors were shooting and they had guns out. It was kinda reckless, and the police department was like, “Yo! We don’t know if this is real or if it’s fake!” So in order to get a video done without being harassed by the police department, you had to get a permit. Then they started controlling where you could shoot, and that kinda sucked too. They didn’t want you to shoot in Times Square or on 125th street in Harlem. They designated areas where there were not a lot of people, so a lot of videos started looking similar because everybody used the same locations, so we had to get creative with that. Me and Lionel always wanted to do something that didn’t look like anything else. It was cool because even though the artist was the star, but there were other people who were stars from the local community – the local thug dude, the local drug dealer dude – they were in the video too, and people watching the videos were like, “Oh shit! That’s such and such!” Or “They shot that over by the bodega on such and such and street”. That’s what made it real.

You can’t even put out a song without a video anymore it seems.

It’s very disposable, the creative process has been put into hyper-mode and you have to do so much stuff just to get noticed. At the end of the day, most artists just want to be noticed, so they just do it to get noticed, instead of thinking about the timing and the process of it. Certain songs that came out in the 80’s and 90’s were great songs and there was no video for it, and you were OK with that! You still loved the song and the artist. It’s like when I’m deejaying, if I’m playing a young crowd, you’re playing a minute or less of a song. But if I’m playing with an older crowd, I play more because they know the words and there’s a certain riff that they like and they’re waiting for that part. Nowadays, the best part is just the first minute of the song, and that’s it! My big thing now is DVD video mixing, which is great because sometimes people have never seen the video to the songs that I play.

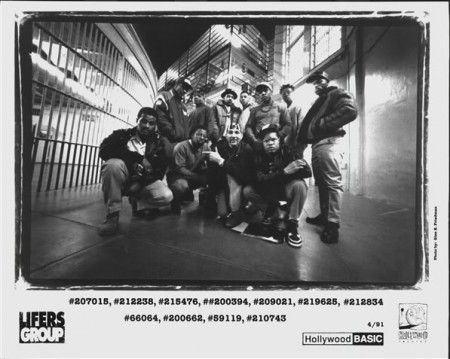

You were involved with the Lifer Group project, right?

The Lifers Group was a great album that was out out by Hollywood Records. We went to Rahway State Prison in New Jersey and I started doing interviews with the guys. They knew so much, they watched Video Music Box all the time because they had TV a certain amount of time. It was big in all the prisons in the area, because the guys used to watch it for the videos as well as the parties, because they were from that particular area. So they might see their girlfriend dancing with some guy, “I knew you were with that guy! I saw you on Video Music Box!” [laughs] It was supposed to be a short thing, but we turned it into an hour special, and we were nominated for an Emmy. My interest in them was there was an album that came out of Rahway Prison by this group called The Escorts in the 70’s. They were a singing group from Rahway State Prison, and I was breaking it down to them. The Escorts have been sampled by Public Enemy and a couple of other groups, they weren’t a rap group, they were a singing group. I followed them for their whole career, so it was a connection for me, it was a big deal.

What was your involvement with the movie Juice?

I was brought in as a consultant and I ended up being made Associate Producer for doing so much in the beginning, because nobody wanted to do the movie, nobody trusted Hollywood like that because of movies like Beat Street. They came to me and said, “Ralph, can you help us out getting people involved?”, because of the popularity of the show. The only person they had was Tupac, because they were from the West Coast, and Ernest Dickerson was the director. He’d worked with Spike Lee as a cinematographer, this was first directing job. I got in contact with Queen Latifah, they couldn’t get the Bomb Squad to do the soundtrack so I got in contact with them, then everybody started coming to the table. I changed the script up a little bit, and I’ve got a little cameo in there as well, when they do the DJ battle, and there’s another scene with Omar Epps and the girl from En Vogue – they were in bed watching Video Music Box. they were watching an interview I was doing with Gil-Scott Heron, who was a hero to me. I put that in the movie, but I didn’t tell him that did it! So Gill calls me up when the movie came out, and goes, “Yo man, did you put me in a movie?” I was like, “Oh shit, I’m trouble!” He was like, “Nah, it’s cool, man. My daughter just went to see this movie called Juice and she said she saw me in the movie”.

How did you start working with $amhill?

I met him through one of the guys that works with me named Kevin Lawrence. Kevin has a radio show on City College and I was going up there, hanging out, and then I met $amhill. Kev said, “$amhill has some music, you should check it out”. I started listening and I was like, “This is unique, his style and his voice”. I’d never heard nobody talking about the shit that $amhill is talking about, and I thought it was pretty interesting. We did the first “Poetic Justice” video, and “Poetic Justice” to me was great. I said, “I’m not sure if everybody is ready for this yet, because of the content. It’s really like a sub-culture. But if you continue doing what you’re doing, you’re going to be a big star”. I did a show that was hosting and Rakim was the headliner, and $am opened up for the show and got a chance to hang out with Rakim. He’s from the South Bronx, he’s been around some of the early artists from that area, he knows from a real grass roots level how music is started. The content is a sub culture that exists but nobody talks about – relationships with women, prostitutes and pimps and drug shit that goes on. He gives you a little window of what that is all about. People are aware of it but some people are not ready for that. “Poetic Justice” is an introduction into that world.

What can you tell me about Brooklyn?

There’s a big Caribbean community there, so any kind of music that you wanted to hear, you could go directly to a real reggae spot and they’re playing hardcore stuff, as well as the artists showing up. So I got to meet guys that I worked with eventually like Shabba [Ranks] or Supercat, I did videos with them. Shaggy used to hang out when he first came home, he was a marine. We used to throw the hottest parties and he used to come down. He became part of this crew called Signet with this guy named Screetchy Dan, Red Foxxx – it was the beginning of the New York reggae scene – and Shaggy became the most successful out of everybody. I did the video for Black Moon’s “Who Got The Props”. Chuck Chillout actually found the group, and he was like, “Yo, you’ve gotta do a video for this”. He brought me the demo of “Who Got The Props”, and I was like, “Yo, this is the shit right here!” They’re from Brooklyn, almost the same experience, influenced by the Lo Life group. From there came Smif ‘N Wessun, where you really started to hear the different sounds that represent Brooklyn. When you really want some culture, you go to Brooklyn and you can find pretty much whatever you wanna find.

What sets Brooklyn apart from other boroughs?

Brooklyn is a little bit more grungy and a little bit more dirty. Any group – I don’t care what it is – that comes out of Brooklyn, if it’s a rock & roll group, if it’s a drum and bass group, they just feel different. It’s a little bit more dirty, it’s a little bit more street. The Bronx almost has the same thing, but they don’t have as many artists that have been successful out of that city. Queens has been the most successful of all the boroughs, sales-wise. They just want it, they’re hungry. They wanna come up. They want to get on. Brooklyn’s always at a party, I don’t care if you’re in London or Australia, there’s somebody from Brooklyn there!

Long Island seems to produce a lot of left-field stuff.

Much more unorthodox stuff. There are probably more rock & roll bands in that area, so when you go into the studio you’re hearing all types of music and all types of production. There’s more of a chance to hear different sounds. Queens and Long Island have the advantage of space. It’s not as crowded, and that gives you a little bit more open-mindedness to try different things. If you’re from the hood, if you’re from the projects, you don’t want to make a mistake. They feel it could be their career. Queens are Long Island are like, “Well, they didn’t like that. Maybe we should try something else”. The Bronx, Manhattan, it’s like, “Nah, that shit is wack, son! You guys aren’t gonna make it!”

Who do you consider the greatest MC of all time?

My favorite is Rakim. If you go with the body of work, it’s Jay-Z. If you go with all-time, it could be LL Cool J, because of the amount of generations that he’s been putting out music on. But my favorite if I’m just putting on music to listen to is Rakim.

Marley Marl – “The Symphony”

Wu-Tang Clan – “C.R.E.A.M”

$amhill – “Poetic Justice”

Good interview!

An average brother can end up sewed into the product in an effort to make a living

I’m glad he called out the Box for biting their name, haha..